“Une des plus merveilleuses manifestations de la nature est l’acte procréant et perpétuant les espèces. Cet acte, laid chez la plupart des mammifères, prend une réelle beauté esthétique avec le félin et s’accompagne alors de cris tels que l’on ne saurait décider s’il s’accomplit dans l’extrême joie ou la douleur extrême.”1

1 François-Rupert Carabin, Une pornographie !! Lettre ouverte à Monsieur le Président de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (without publisher, 1913), s.p. Emphasis in the original.

Feline Sexuality

In 1913, Alsatian-born artist and artisan François-Rupert Carabin felt compelled to take the public stance quoted above. What had happened? “Cara,” as his friends casually called him, had submitted a wood carving entitled Nocturne (Fig. 1) to the Salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Art that same year. The work was brusquely rejected by the jury.

Fig. 1: François-Rupert Carabin, Nocturne, Strasbourg, Musée d’art moderne et contemporain, 1913, © Service photographique interne des musées de la Ville de Strasbourg/Musée d’art moderne et contemporain de la Ville de Strasbourg.

The small-format wooden sculpture, measuring 42 centimeters in length and 22 in width—thus nearly life-sized—was carved with dexterous precision from pearwood and depicted two copulating cats. The lower animal presses its belly against the wooden base, its front paws clawing at the narrow edge. Its entire musculature is visibly tensed, and its finely contoured neck stretches outward—whether this stretch moves forward in resistance or trustingly backward toward the second animal remains, in keeping with Carabin’s quotation, meaningfully unresolved. From behind, the second cat nestles against the first. Its front paws are pushed beneath the other’s belly, resting on the base, and again it is purposefully ambiguous whether the gesture is an intimate embrace or a forceful immobilization. Its head, likewise ambiguous, rests at an angle against the neck of the lower animal, whose eyes are closed in an expression of intense sensuality.

The jury allegedly deemed the small work “un peu trop réaliste”2 and therefore unacceptable for the standards of the institution and its audience. Certainly, the tension in the hind legs of the mounting cat, the muscular tautness of both bodies, and the phallic erection of the tail all strongly suggest a sexual reading of the scene. Carabin—who was frequently praised for a humor that was at times subtle, sometimes witty, and often, from today’s perspective, deeply misogynistic—found the rejection anything but amusing. Although Carabin was never formally canonized by art history as a major figure, during his lifetime the “Benvenuto Cellini de notre temps”3 was considered one of Montmartre’s most renowned artists. He moved in circles that included Joris-Karl Huysmans, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Claude Monet, Jules Dalou, Auguste Renoir, Auguste Rodin, Loïe Fuller, and Cléo de Mérode; both Manet and Émile Gallé purchased his works. He co-founded the Salon des Indépendants and played a key role in ensuring that, beginning in 1891, the esteemed Salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts began accepting decorative art objects for exhibition.4 In 1893, he was awarded the prestigious Palmes académiques, and in 1903 he received the Légion d’honneur—one of the highest honors bestowed by the French Republic. It is only with this context in mind that one can fully grasp the affront the rejected cats represented for Carabin. From his perspective, it was nothing short of an arrogant act of lèse-majesté.

2 Cf. Nadine Lehni and Étienne Martin, eds. François-Rupert Carabin 1862-1932 (Éditions des Musées de la Ville de Strasbourg, 1993), 62.

3 Gustave Coquiot, “Rupert Carabin,” La Presse, August 1, 1900, [3].

4 Cf. Colette Merklen-Carabin, “Rupert Carabin,” in L’œuvre de Rupert Carabin: 1862-1932, ed. Yvonne Brunhammer (Idea Books, 1974), 48-52; Henri Heitz, “Carabin François Rupert: Sculpteur (1862-1932),” Pays d’Alsace 200, (2002).

Outraged and citing all of his distinctions, Carabin wrote a pamphlet that same year titled Une pornographie !!, in which he published his correspondence with the jury and allowed himself a rare moment of artistic self-reflection. Art, he argued, must always be a materialization of the ideal (“ideal”), and with this work, he specifically intended to draw attention to the fact that the social state—and especially positivist science—was presently stifling every form of idealism at its root.5 The quotation that opens this essay follows directly in the pamphlet, fusing the aesthetic quality of feline sexual acts with an ambiguity between maximum pleasure and extreme pain that actively resists the demand for scientific clarity. Sex among cats, he wrote, possessed a particularly distinctive “beauté esthétique.” The pamphlet also included four photographs of the scandalous cats, taken from different angles, intended to provide visual evidence in support of his textual claims.

5 Cf. Carabin, Une pornographie !!, s.p.

In doing so, Carabin was invoking a familiar turn-of-the-century motif: the cold, humorless “Weltbesiegerin unserer Tage, die Naturwissenschaft,”6 the natural sciences, were suspected of rendering all forms of artistic creativity and semantic openness impossible.7 His argument, knowingly or not, ignored the fact that psychophysiology in France had, throughout the latter half of the 19th century, feverishly pursued the problem that pleasure and pain are often indistinguishable from one another on the surface and in the moment. As early as 1862, Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne had demonstrated that nearly identical muscle groups were responsible for corresponding facial expressions in experiences of pleasure and pain.8 Carabin’s vocabulary—“procréant,” “espèces,” and “mammifères”—itself evokes the register of biological natural science, whether he intended it or not. In this way, he inscribes his wooden cats—again, likely intentionally—into a scientifically reverent fascination with the eroticism of pain that predominated in literary Symbolism.9

6 Emil du Bois-Reymond, Über die Grenzen des Naturerkennens (Veit und Co., 1872), 1.

7 Cf. Thomas Moser, Körper & Objekte: Kraft- und Berührungserfahrungen in Kunst und Wissenschaft um 1900 (Wilhelm Fink, 2022), 250-259.

8 Cf. Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne, Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine ou Analyse électro-physiologique de l’expression des passions applicable à la pratique des arts plastiques (Jules Renouard, 1862), 40.

9 Cf., for instance, Anne-Rose Meyer, Homo dolorosus: Körper – Schmerz – Ästhetik (Wilhelm Fink, 2011), 289-97; Thomas Moser, Das Primat des Körpers: Eine Psychophysiologie der Schmerzerotik im Fin de Siècle (Universitätsbibliothek LMU München, 2016).

Nonetheless, the influential art critic Pascal Forthuny defended Carabin in the Cahiers de l’art moderne in 1913, highlighting and appreciating the very ambiguity the artist had demanded. “Imaginez deux chats—des matous—dans une attitude un peu lascive (c’est l’heure des gouttières), mais tel qu’il fallait, pour voir et comprendre, s’y reprendre à deux fois comme on dit.”10 One must look twice, in other words, to understand what is actually being shown. And that, he concluded, was evidence of Carabin’s extraordinary capabilities as an artist.11 More interesting than this art-theoretical sophistry, however, is Forthuny’s use of the word “matous,” a colloquial term that distinguishes male cats from females. Perhaps the critic identified them as such on the basis of their phallic tails—but regardless of the reason, the scene, which was already sexual in nature, becomes charged with homoeroticism.12

10 Pascal Forthuny, Cahiers de l’art moderne 2, (1913), quoted from Yvonne Brunhammer, ed. L’œuvre de Rupert Carabin: 1862-1932 (Idea Books, 1974), 153.

11 On the dictum of semantic ambiguity in French art around 1900, see Dario Gamboni, Potential Images: Ambiguity and Indeterminacy in Modern Art (Reaktion Books, 2002).

12 Cf. also Sarah Sik, “Seeking New Sins: The Erotic Deco-Sculptural Work of François-Rupert Carabin,” IV coupDefouet International Congress, 2015, https://www.artnouveau.eu/admin_ponencies/functions/upload/uploads/Sarah_Sik_Paper.pdf.

This interpretation is doubly disconcerting—not because of the implication of homosexuality per se, but because of the assumption that both animals are male. For Carabin was thoroughly obsessed with feline imagery coded as feminine. He featured it, for instance, on a chased silver belt clasp—thus placing it near the genital area—, on a piano of his design (Fig. 2), and even as sculpted armrests on a elaborated fauteuil whose figurative program was overtly misogynistic (Fig. 3).13 Even his carved, naked allegory of Volupté (Fig. 4) features, tellingly, a cat at her feet alongside a monkey. In The Troubled Republic, Richard Thomson has thoroughly demonstrated that the fin de siècle in general, and the Decadent movement in particular, conspicuously used the elegant, seemingly hedonistic and capricious cat as a symbol for female sexuality.14 It is well known that the French term for female cats (“chatte”) has long served as a vulgar slang term for the female genitals, so much so that people often deliberately refer to male cats (“chat”) instead, simply to avoid uttering the other word. In this context, the Belle Époque cultivated a bawdy visual culture in which cats were frequently placed on or near the laps of women as part of image-word play alluding to their sexuality and gender.

13 Cf. Rodolphe P. A. Darzens, “Notes sur les ouvriers d’art: R. Carabin,” L’art moderne, (1895); Thomas Moser, “Embodied Experiences of Force. Carabin’s Anthropomorphic Fauteuils and the ‘Muscular Sense’ in late 19th Century Medicine,” in Energetic Bodies: Sciences and Aesthetics of Strength and Strain, ed. Thomas Moser and Wilma Scheschonk (de Gruyter, 2022); Moser, Körper & Objekte, 145-210.

14 Cf. Richard Thomson, The Troubled Republic: Visual Culture and Social Debate in France 1889-1900 (Yale University Press, 2004), 54-56.

Fig. 2: François-Rupert Carabin, Piano (detail), Paris, Musée des arts décoratifs, 1913, © dalbera/Wikimedia Commons.

Fig. 3: François-Rupert Carabin, Fauteuil, Strasbourg, Musée d’art moderne et contemporain, 1893, © Service photographique interne des musées de la Ville de Strasbourg/Musée d’art moderne et contemporain de la Ville de Strasbourg.

Fig. 4: François-Rupert Carabin, La volupté, Strasbourg, Musée d’art moderne et contemporain, 1902, © Service photographique interne des musées de la Ville de Strasbourg/Musée d’art moderne et contemporain de la Ville de Strasbourg.

From a cultural-historical perspective, this makes it much easier to understand why the jury refused to exhibit two cats entwined so intimately. Around 1900, cats were an unmistakably sexualized motif, one that could not be neutralized by attributing it to the zoological ambitions of artists specialized in animal subjects. Even more precarious from a heteropatriarchal viewpoint was the fact that Carabin’s cat couple also flirted with homosexuality—an orientation the avant-garde approached with deep ambivalence. On the one hand, such desires were pathologized and taboo within society; on the other, it was precisely this precarity that exerted a powerful fascination on a Decadent culture obsessed with social distinction and transgression. It is no coincidence that these circles were equally enthralled by the studies of Krafft-Ebing and the rediscovered literary excesses of the Marquis de Sade.15 Carabin was a tactile-obsessed artist whose career rested primarily on lascivious representations of women—figures that were literally made to be handled by his predominantly male clientele, as cane handles, silver rings, or statuettes. That this particular artist should have taken offense at a supposedly frivolous appropriation of his cats seems, to say the least, questionable.

15 Cf. Richard von Krafft-Ebing, Psychopathia Sexualis: Eine klinisch-forensische Studie (Ferdinand Enke, 1886); Maurica Banchot: Lautréamont et Sade (Éditions de Minuit, 1949); Lawrence W. Lynch: The Marquis de Sade (Twayne Publishers, 1984); Moser, Das Primat des Körpers; Martin Urmann, Dekadenz: Oberfläche und Tiefe in der Kunst um 1900 (Turia + Kant, 2016).

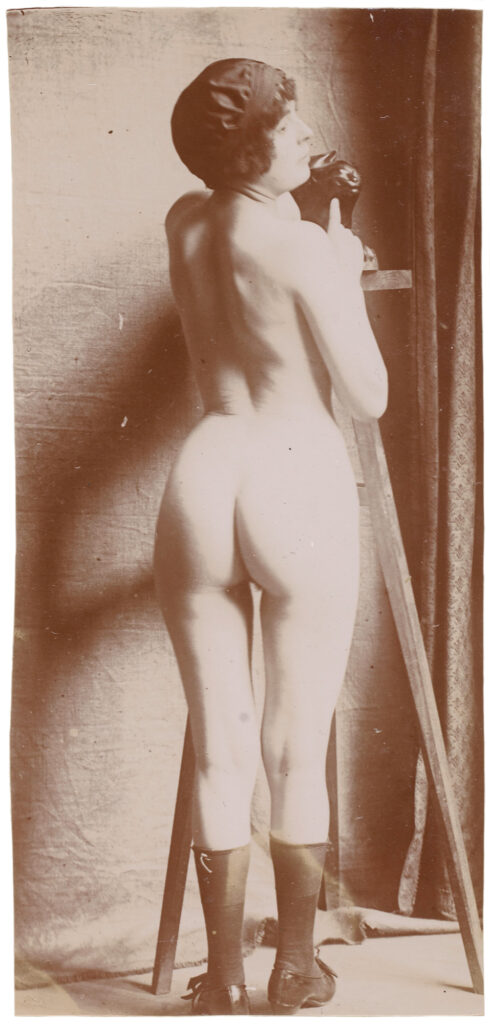

In the past ten to fifteen years, scholarship has increasingly turned its attention to Carabin’s photographic practice. The Musée d’Orsay in Paris holds several hundred prints and negatives of photographs the artist took of his exclusively female models in his studio. In his pioneering essay on this collection, Étienne Eichholtzer has already addressed the fact that one of these photographs (Fig. 5) depicts a nude model posing with Nocturne.16 The woman—wearing only a head covering, stockings, and half-shoes, which only emphasizes her state of undress—has turned her back to Carabin’s ontological assemblage of eye and camera, with her torso slightly twisted to the right so that her face is seen in profile. Directly in front of her, and in front of a flat curtain backdrop, stands a three-legged wooden tripod on which rests the controversial cat sculpture. The model’s right index finger touches the cheek of the lower cat, as if gently stroking it. In this gesture—likely playful, carried out in the intimate setting of the artist’s studio—the ambiguity between pain and pleasure is dissolved. The cat’s head, tilted back, is frozen in the image as if enjoying a caress. Yet the constellation is, as mentioned, highly sexually charged: in pressing the shutter, Carabin initiated a masturbatory and above all lesbian reinterpretation of his cats—whether he directed the gesture himself or whether it emerged spontaneously from the model remains unclear.17 But at the latest in this photograph, lesbian sexuality begins to clearly emerge from Nocturne’s feline sexuality.

16 Cf. Étienne Eichholtzer, “Le regard érotique: Le fonds photographique François-Rupert Carabin (1862-1932),” Études photographiques 33, (2015), http://journals.openedition.org/etudesphotographiques/3555.

17 Cf. Eichholtzer, “Le regard érotique,” s.p.

Fig. 5: François-Rupert Carabin, Femme nue posant devant Nocturne, Paris, Musée d’Orsay, between 1913 and 1915, © Alexis Brandt/Musée d’Orsay.

Pandora’s Box

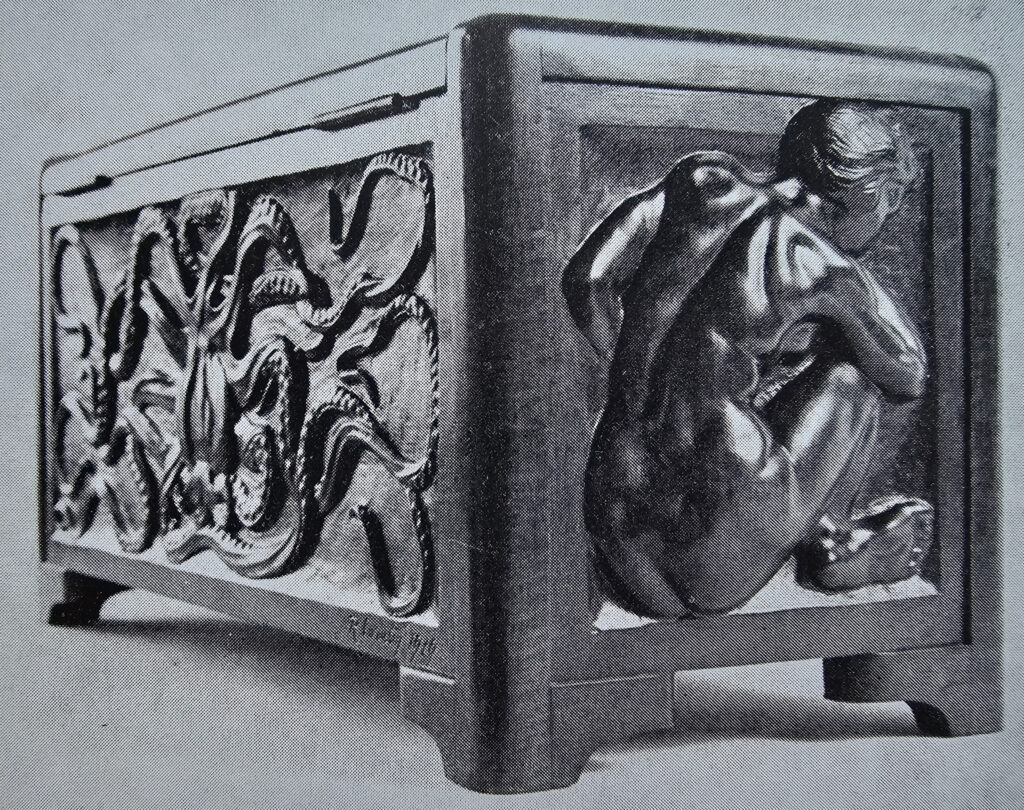

Colette Merklen-Carabin, the artist’s daughter, was the first to draw attention to the connection between Nocturne and another work by her father in a 1974 exhibition catalogue.18 More precisely, the ensemble consists of two works: a wooden box measuring 58 by 28 centimeters (Fig. 6), intricately decorated and carved from walnut, and a wooden sculptural group (Fig. 7) depicting two nude female figures engaged in cunnilingus—a motif Carabin had previously explored in 1892 in the form of a silver ring, though that version featured a male and a female figure. Executed in the same material as the nocturnal cats, this later sculpture presents a woman with bent legs, her chest arched upward in ecstasy, her head thrown back. One arm covers her face in a gesture of overwhelming rapture. Between her open thighs rests the head of a second woman, spread out beneath her, whose arms tucked beneath the first woman’s hips visually echo the front paws of the upper cat in Nocturne. In a certain sense, Carabin was spelling out in 1918 both the motif and the artistic shamelessness for which he had been accused in 1913. A scandal was not only foreseeable but, it seems, fully calculated. What’s particularly imaginative is that Carabin did not exhibit the pair openly but instead smuggled them into the Salon, hidden inside the aforementioned box.

18 Cf. Merklen-Carabin, “Rupert Carabin,” 46.

Fig. 6: François-Rupert Carabin, Coffre, whereabouts unknown, 1919, © Laurent Sully-Jaulmes.

Fig. 7: François-Rupert Carabin, Deux femmes, private collection, 1918, © Laurent Sully-Jaulmes.

The box’s whereabouts are unknown today, but two photographs and a note from the 1974 exhibition catalogue still exist. On one of the narrow sides, a relief shows a nude female figure, crammed into an uncomfortable pose with her back turned to the viewer—in classic Carabin fashion. On the front side, from which the double-hinged lid could be opened, Carabin carved another relief in the form of an octopus flattened decoratively across the surface. On the top of the lid, the following inscription is engraved in large letters: “Regard chaste laisse-moi clos.”

What exactly happened with the wooden box during the Salon exhibition is not known. Following Merklen-Carabin, the box had a deliberately easy-to-open lock, and the organizers apparently only requested its removal after it had already been placed on display.19 It can therefore be assumed that it was originally shown in closed form and that visitors approached the object and opened it themselves. According to his daughter, Carabin responded to the jury by arguing that he certainly had the right to exhibit a closed chest—and suggested, tongue in cheek, that two guards be posted nearby to prevent overly curious viewers from peeking inside. As Étienne Eichholtzer has noted, the anecdote fits perfectly into the image of Carabin as the ironically subversive enfant terrible of the bourgeois art world.

19 Cf. Merklen-Carabin, “Rupert Carabin,” 46.

But there is much more to unpack here. Until now, scholars have largely overlooked the fact that Carabin was deliberately referencing the myth of Pandora—and for that reason, the object (or rather the ensemble of two objects) ought rightly to be titled Pandora’s Box, even though it has previously been listed under the descriptive titles Coffre and Deux femmes.20 According to Hesiod’s version, the myth recounts Zeus’s plan for revenge after Prometheus steals fire from the gods: Pandora and her jar play the central role.21 The father of the gods places all the world’s evils, along with hope, into a vessel—a jar later mistranslated by Erasmus of Rotterdam in the Adagia as a box—and sends them to earth via the first woman. Hephaestus fashions Pandora from clay, and the other gods bestow upon her various gifts, including beauty, curiosity, and rhetorical skill. Epimetheus marries her despite Prometheus’ explicit warning never to open the jar. Ultimately, Pandora succumbs to temptation, opens what would become the proverbial box, and releases moral evils, plagues, death, and disease into the world—specifically, upon men. That Pandora released both the evils and her own curiosity from Olympus into the human world was passed down as a narrative that fused femininity with danger and became a foundation for the fin-de-siècle archetype of the man-consuming femme fatale.

20 Brunhammer, L’œuvre de Rupert Carabin, 156-57; Lehni und Martin, François-Rupert Carabin 1862-1932, 63.

21 Cf. Hesiod, Werke und Tage, ed. and transl. Otto Schönberger (Stuttgart, 2004); Lilah-Grace Fraser, “A Woman of Consequence: Pandora in Hesiod’s Works and Days,” The Cambridge Classical Journal 57, (2011).

The inscription on Carabin’s lid clearly references Zeus’s rhetorical warning that the vessel must remain closed. Sarah Sik translates the inscription as “If you regard your chastity, leave me shut,” but this rendering is misleading, as “Regard chaste, laisse-moi clos” does not form a conditional clause. Here, “regard” is a noun—the addressee is not the viewer but the chaste gaze itself. The box speaks directly to the audience in the tradition of premodern inscriptions, mischievously muddling sensory registers and, in so doing, the interests of its viewers. A gaze cannot open a box—and around 1900, the applied arts were no longer aimed at the kind of disembodied, intellectual pleasure Kant or Wackenroder once theorized. Carabin’s objects were purchased to be lifted, turned, stroked, touched, and used. In short, Carabin worked as much for the hand as for the eye—even if in exhibition contexts that haptic dimension was often frustrated. Among the highest pleasures of the tactile sense are precisely those erotic and embodied sensations that Carabin barely concealed within his chest.

This ambivalent aesthetic experience is reinforced by the sculptural decoration: the female nude on the narrow side of the chest, with her back turned to the viewer, denies visual access in accordance with the inscription and instead offers, in return, a voluminous, tactile female body to hands implicitly imagined as male. On the opposite side, the octopus—an enigmatic creature rendered as a spectacular haptic relief—is displayed. Since mid-century zoological studies and Victor Hugo’s Les Travailleurs de la mer (1866), the octopus had been considered both highly sensitive to touch and increasingly symbolic of female sexuality.22 Fittingly, the eight interlaced tentacles on the outside anticipate the eight interlocked limbs of the figures hidden within. – The box thus points toward the sensual pleasures it conceals and leaves their revelation up to the viewer’s own moral self-evaluation: visitors to the exhibition were ultimately responsible for proving the chastity the jury claimed to uphold.

22 Cf. Moser, Körper & Objekte, 93-144.

By explicitly invoking the Pandora myth, Carabin also inscribed himself into its constellation. For it was Hephaestus—the craftsman among the Olympians—who was tasked with creating the first woman. Unsurprisingly, the myth of Pandora has often been linked with the sculptor’s myth of Galatea and Pygmalion, as well as with the divine creation of Eve from Adam’s rib—a bodyfashioned by another, and thus always already a crafted artifact.23 In the fin-de-siècle imagination, this self-image of the male artist as a quasi-divine procreator was especially powerful, combining sexual, creative, and moral authority.24 Without Hephaestus’s craftsmanship, the gifts of the other gods—and Zeus’s revenge—would have amounted to nothing. In this figure, Carabin sees both his artisan identity and the aggrieved divine father whose warning he engraved into a utilitarian object. And, as the one who delivers the box, he is part Pandora, too—if one wishes to carry the analogy that far.

23 Cf. Stella P. Revard, “Milton and Myth,” in Reassembling Truth: Twenty-first-century Milton, ed. Charles W. Durham and Kristin A. Pruitt (Susquehanna University, 2003), 37.

24 See, for instance, Matthias Krüger, Christine Ott and Ulrich Pfisterer, eds. Die Biologie der Kreativität: Ein Produktionsästhetisches Denkmodell der Moderne (Diaphanes, 2013); Matthias Krüger, Das Relief der Farbe: Pastose Malerei in der französischen Kunstkritik 1850-1890 (Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2007), 176-79; Patricia Matthews, Passionate Discontent: Creativity, Gender, and French Symbolist Art (University of Chicago Press, 1999).

At the same time, the iconography of the box reflects Carabin’s own position and draws attention to the conditions of reception. With his Pandora’s Box, Carabin thus negotiates his own “act of creation,” and through the interplay between sculptural form and textual inscription, he draws the exhibition-going public into a reflexive relation that includes the art world itself as a structuring frame. The work not only anticipates the institutional scandal that had erupted repeatedly over depictions of sexuality since the founding of the first Paris Salon during the Ancien Régime, but it exhibits that very scandal. Neither the box nor its contents, Carabin insists, are inherently transgressive; rather, the fault lies in an inappropriate reception. In this case, at least, the public had the opportunity to search for hope at the bottom of Pandora’s box—hope that, in Hesiod’s telling, remained locked away. Years after the scandal of the cats, Carabin, with evident irony, continues to disavow all artistic responsibility.

It would be tempting, and not unjustified, to once again launch into a moral critique of Carabin’s appalling misogyny and to expose the heteropatriarchal dominance of male artists over modern femininities.25 Why Carabin placed a sapphic scene in Pandora’s box cannot be definitively answered. It most likely stems from the already homoerotic connotation of the liaison in Nocturne. And one can reasonably assume—without requiring any psychoanalytic framing—that what we are dealing with is a cis-male sexual fantasy, one that could be consumed voyeuristically by a heterosexual audience, rather than a serious condemnation of lesbian love as apocalyptic sin.26 For all his flirtation with socially nonconforming Decadence, Carabin offers no opening to a queer reading of himself—as has become possible in the cases of Jean Lorrain, Robert de Montesquiou, John Addington Symonds, or Oscar Wilde. If anything, Carabin—one of the great erotomaniacs of the fin de siècle—appears almost incapable of representing male sexuality.27 Time and again, in his decorative objects, male hands are meant to rest on female-back fauteuils, phallic fountain pens are to be inserted into inkwells in the form of women’s bodies. But these sexual intrusions remain latent in the works themselves and must be completed by male recipients. Thus emerges the paradox that the homosexual scene in Pandora’s Box became necessary not despite but because of the artist’s homophobia. Perhaps, too, because men—within the sexual act—lack the “beauté esthétique” that was all too close to Carabin’s heart.

25 Cf. Sik, “Seeking New Sins”; Nadine Lehni, “‘…quant aux femmes de ces histoires, pourquoi ne seraient-elles pas diaboliques?,’” in François-Rupert Carabin 1862-1932, ed. Nadine Lehni and Étienne Martin (Éditions des Musées de la Ville de Strasbourg, 1993).

26 Research on cis-male consumption of lesbian sexuality in pornography, for example, has been examined in every conceivable direction by both Freud and Lacan, and the corresponding studies fill entire cupboard walls. An early introduction to the discourse is offered by Peter Benson, “Between Women: Lesbianism in Pornography,” Textual Practice 7, no. 3 (1993). Using the example of lesbian acts in cis-male pornography, Benson already discusses the fact that observed sexual acts can also be appreciated by cis-male recipients without a male actor – without identification personnel, so to speak. Freudian readings had long assumed that this must necessarily be followed by some form of punishment or reprimand, as it was assumed that sexual acts between women would be perceived as sexual acts withheld from a man.

27 Cf. on the perception, staging and pathologization of lesbian sexuality in the art and literature of fin-de-siècle Paris, authoritative Nicole Albert: Saphisme et décadence dans Paris fin-de-siècle (Éditions de la Martinière, 2004).